HIV stigma in the workplace

A couple of weeks ago, Dr. Kai Jonas and myself (Martijn Bruil) made a number of national newspapers with a small study we did on HIV stigma. It was related to the AIDS Impact conference held end of July in Amsterdam. During the conference all scientist doing research on the impact of HIV prevention, infection, AIDS, treatment, etc, join to share the status around the world. While in Western European countries, HIV and AIDS might seem a small problem that very little people suffer from, worldwide the epidemic is still growing, also in new regions like Eastern Europe and Asia. So research on HIV/ AIDS is still very relevant!

In the Netherlands, it is estimated that around 25.000 people are HIV infected, of which around 19.000 know and are treated (and 6.000 people do not know, because they don’t get tested). The ones that have HIV but do not test for HIV, create the biggest risk for spreading the infection. Around 1.100 new HIV+ diagnoses are done yearly. So it’s very important to get tested regularly if you are part of a risk group! Around 50 people a year still die of AIDS in the Netherlands. That does not sound like a lot, but is still 50 too many.

We wanted to know how ‘big’ the issue of HIV stigma is in the Netherlands. Since people living with HIV are being treated now with medicine cocktails, their health and quality of life has improved tremendously. And a lot of people with HIV can live their life pretty normal and work as well! How normal is it however to be a person with HIV working in a company? What do you colleagues feel and know about that? We wanted to find out by asking our Amsterdam Pink Panel about their experiences with colleagues living with HIV. The results were interesting to say the least. A small summary is outlined below: I cut out all the statistical information not relevant for general readers but the poster we presented at the conference can be found on my website (click here).

Set up of research

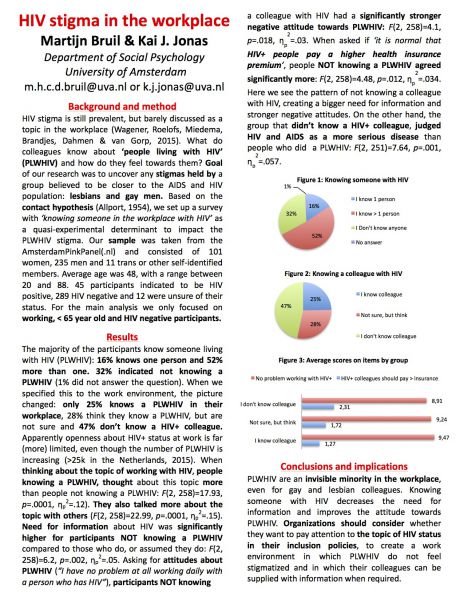

Goal of our research was to uncover any stigmas held by a group believed to be closer to the AIDS and HIV population: lesbians and gay men. Based on the contact hypothesis (Allport, 1954), we set up a survey. Our sample was taken from the AmsterdamPinkPanel(.nl) and consisted of 101 women, 235 men and 11 trans or other self-identified members. Average age was 48, with a range between 20 and 88. 45 participants indicated to be HIV positive, 289 HIV negative and 12 were unsure of their status. For the analysis we only focused on working, < 65 year old and HIV negative participants.

Results

The majority of the participants know someone living with HIV: 16% knows one person and 52% more than one. 32% indicated not knowing a person living with HIV (1% did not answer the question). When we specified this to the work environment, the picture changed: only 25% knows a person living with HIV in their workplace, 28% think they know a person living with HIV, but are not sure and 47% don’t know a HIV+ colleague. Apparently openness about HIV+ status at work is far (more) limited, even though the number of people living with HIV is increasing. We also asked people how much people they thought were living with HIV in the Netherlands and how many people in the Netherlands still die from AIDS per year.

When thinking about the topic of working with HIV, people knowing a HIV+ person, thought about this topic more than people not knowing a person living with HIV. If you know someone who is HIV+, you also talked more about the topic with others. Need for information about HIV was significantly higher for participants NOT knowing a person living with HIV compared to those who do, or assumed they do. Asking for attitudes about people living with HIV (“I have no problem at all working daily with a person who has HIV”), participants NOT knowing a colleague with HIV had a significantly stronger negative attitude towards HIV+ colleagues.

When asked if ‘it is normal that HIV+ people pay a higher health insurance premium’, people NOT knowing a PLWHIV agreed significantly more. Here we see the pattern of not knowing a colleague with HIV, creating a bigger need for information and stronger negative attitudes. On the other hand, the group that didn’t know a HIV+ colleague, judged HIV and AIDS as a more serious disease than people who did know a person living with HIV.

Conclusions and implications

What does this all mean? What do we want from this? This is also what the journalist asked us. For one, it means that people living with HIV are an invisible minority in the workplace, even for gay and lesbian colleagues. For people who are HIV+ this might lead to feeling less secure and free in the workplace. Maybe not sure to tell other people or not or unsure about the reaction of the management and company. On the side of the colleagues it means knowing someone with HIV decreases the need for information and improves the attitude towards people living with HIV.

Organizations should consider whether they want to pay attention to the topic of HIV status in their inclusion policies, to create a work environment in which people living with HIV do not feel stigmatized and in which their colleagues can be supplied with information when required. More research is needed and that is exactly what we hope to do in the near future to determine – together with working HIV+ people and organisations – what needs to be done to limit the negative effects of stigma.

For now – having these articles in the newspaper already made more people aware of the issue and hopefully opened up some doors (or small windows?) to talk about this topic.

Research: Talking to your partner pays off

Keeping quiet about difficult topics with a relationship means less trust, more stress and frustration: sex and money are the most sensitive topics for couples.

Over 100 participants filled out the survey about ‘difficult topics in relationships’. 64% were females and 36% were males between te ages of 30 and 65. We had an experienced panel: none of the participants was in a relationship shorter than a year and 36% had even been together for over 20 years. 68% was currently married and 70% had a previous relationship before with another partner. 58% had children. When asked if they had been unfaithful tot heir current partner, 36% answered ‘yes’ and 59% ‘no’ (5% chose not to answer). What have we learned from this group of participants?

Difference between ‘Talkers’ and ‘Non-talkers’

54% of the participants have the feeling they can talk about most issues with their partner, but indicate one of more difficult topics. 40% of the sample chose several topics that were hard to discuss. Only 6% indicated there were no taboes in their relationship and they talked about everything. When asked if it is normal to have secrets for your partner in a relationship, the response is neutral: they don’t agree or disagree very strongly. In the results we find a sort of split between a group of people that do talk about (most) difficult topics and people that do not talk about this.

Looking at the not-talking couples, the problem mainly seems to be a lack of interaction between the two. These participants indicate they try to address touchy subject with their partner, but the conversation does not really start. Their partner often gets angry if they bring something up and therefore they are reluctant to do so. What stands out, is that these participants do not blame their partners for not wanting to talk: they indicate that they probably make ‘too much of an issue’ out of that topic, compared to their partner. Their level of trust in their partner is therefore not much lower that on average. The level of trust in the relationship (whether or not it will last), is significantly lower however and these participants also indicate they feel limited in their development as an individual and as a couple. They strongly believe talking about the hard topics will bring relief.

We also see that people that think it’s normal to keep a secret from their partner, more often hopes that this partner will bring up the difficult subjects. When something is hard to talk about, we would rather keep it a secret till someone else mentions it.

For the couples that do talk about most topics, we unravelled a different pattern. They show significantly more trust in their relationship than the not-talkers and specifically take the time to discuss things. There are just a few or even no topics that are hard to discuss and therefore they do not feel this bothers their personal development or their growth as a couple. More often they are the ones that start the hard discussions, instead of procrastinating: better to get it out of the way! Talking really relieves, they strongly agree. If they would catch their partner lying about something, it could be a reason to end the relationship.

What are the sensitive topics?

For the 94% of the participants that marked topics that are difficult to address, 30% mentioned sex and 20% mentioned money. Also ex-partners and ‘thing that happened in the past’ can be tricky for partners to discuss (both around 15%).

Difference between females and males, gay and straight

The differences between the men and women answering the survey are limited. Women believe more strongly than men that talking about topics will cause relieve. On the other hand, men more often think that discussing a difficult topic could lead to their partner leaving them. When it comes to the content of the sensitive topics women and men agree: sex and money! The differences lie in the way the tasks are divided at home - no issue for any of the men, but for 11% of the women it is – and the way women value attention for each other and spirituality a bit more and the men think ex-partners, things from the past, marrying (or not) and faithfulness are more difficult.

For gay participant faithfulness is also high on the topic list next to sex and money compared to their straight peers, as is spending patterns, romance and things that happened in the past. But dividing tasks in the house, raising children, dealing with family or work-related issues, cause no problems. Sexual preference does not seem to influence being either a talker or a non-talker, nor does it affect the level of trust in the relationship.

Conclusion: Talking Pays Off

Based on this (limited) research project we can conclude that even though it is sometimes hard to do, talking with your partner pays off. The clear difference between the patterns for talkers and non-talkers indicates a threshold – not taking that threshold can lead to partners growing apart: more secrets, less trust and frustrated development.

Especially for sensitive topics, like sex or money, talking together increases mutual trust and strengthens the relationship both on an individual level and as a couple. ‘Talkers’ consciously take the time to talk and often start up the discussion about sensitive topics themselves, creating an ongoing dialogue. They know already that talking relieves stress!

Many participants indicated they can’t talk about difficult topics because their partner might get upset or angry. This could be a handy tactic from that partner to never have to talk about these things again. But for the person that wants to talk, this can have very negative consequences. The threshold to talk at all builds up and they shut down more and more about different topics. They believe the cause for this lies within themselves. They rationalise the problem away by reasoning that the topic must not be ‘that important’ to talk about. This causes the trust in the relationship to diminish and frustrates their personal development. People will tend to keep more secrets from each other, hoping the other one will address the issue one day. Often this doesn’t happen at all and people start living their own lives. As hard as it may seem, these people really need to take the time to talk to each other, if necessary with a coach.

More about Martijn & research

Since 2013 I am doing my PhD research at the University of Amsterdam as a Social Psychologist. My research covers stress experienced by minorities in work situations and the way they deal with that. Is it possible that this stress also leads to positive outcomes?

I am also a member of the Kurt Lewin Institute, the Graduate School from five different universities in the Netherlands. At the KLI I follow different courses and training sessions to become a better scientist!

On this website, I also do surveys about topics I come across during my consultancy and coaching work and that make me curious. Above you can see the questionnaires and results.